Media Hub

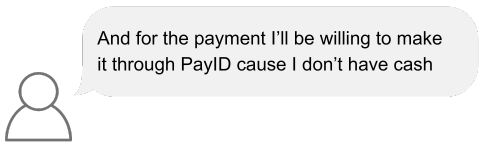

No problem, his brother can pick it up. Sure, I’ve used PayID before and it worked well! I provided my mobile number to John 2.

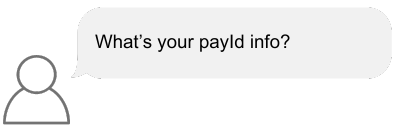

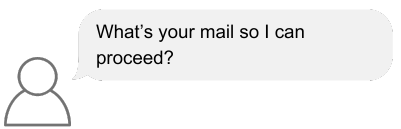

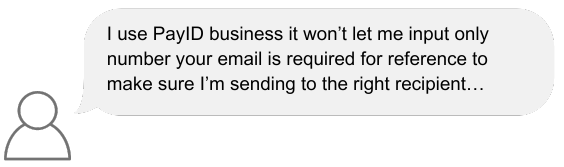

That’s strange – I thought only a phone number OR an email address is required for PayID payment, not both. Ok, this was starting to raise red flags.

John 2 pressured:

After a frantic online search for “PayID scams,” I found numerous warnings. NAB News reported a “new PayID scam targeting Australians selling online.” Consumer and Business Services SA noted scammers often claim someone else will pick up the item due to schedule conflicts and insist on using PayID, sometimes sending convincing texts and emails. A January CHOICE article detailed how these scammers operate: they quickly agree to buy, insist on PayID, fabricate payment issues, and then request fees or reimbursements, even though PayID is free and without tiers.

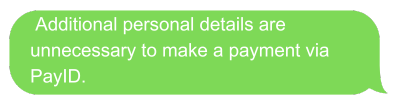

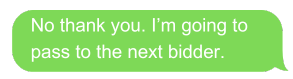

I responded, apprehensive about my knowledge of PayID:

Enough was enough. I ended it there.

John 2 had kept me on the hook for 20 minutes, spinning hopes of a smooth sale, snack money and a clean living room.

Over the next few days I ruminated on this exchange. I nearly fell for it.

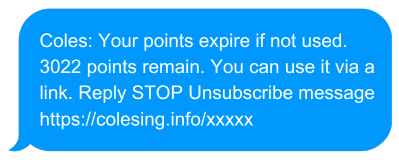

The John 2 fiasco reminded me of the daily bombardment of scam texts and emails that never let up, usually without hesitation I hit “Delete and Report Spam”. However, my mother-in-law admitted she clicked on a suspicious Coles link just yesterday.

Then there are my parents, who, in their 70s were recently scammed via a small regular transaction amount direct-debited from an organisation they’ve never heard of, dealt with, nor signed up to, and operating from a virtual office in Queensland.

After three years of credit card charges going unnoticed, my dad took matters into his own hands, the company arbitrarily agreeing to pay half of the charges back in instalments. Dad did not report this to the government.

Scams pervade our emails, mailboxes, and text messages. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Personal Fraud Survey, over half a million Australians fell victim to scams in 2022-23, a figure that has remained constant over time.[1]

However, in that same year the ABS stopped collecting data about how many Australians encounter scams or the types of scams they face. We don’t know how many Gumtree users nearly fell for scams or how many receive fraudulent links like those from “Coles.” This lack of data means we can’t gauge the full extent of the issue, including the platforms scammers target, whether consumers are becoming savvier, or if scams are becoming more sophisticated.

Reports from credible government agencies including the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) National Anti-Scam Centre (NASC) [2],[3] suggest a decrease in both the prevalence and financial losses due to scams (it’s still in the billions of dollars lost each year by the way), which has been celebrated as a sign of the Government’s successful anti-scam efforts.[4] But, this is in contrast with the ABS findings, which indicate a significant decline in the rate of Australians reporting scams to government agencies. This discrepancy prompts me to wonder about the many unreported incidents, such as my father’s. A recent report released by CHOICE found that only half of scam victims even made contact with their bank about the scam after it was identified.[5]

Lastly, the ABS and the ACCC have different definitions of what constitutes a “scam”. The ACCC includes identity theft as a type of scam, but the ABS counts this separately. While the Government defines a scam a certain way (or two), what does the average person consider and detect as a “scam”? What do you consider a scam?

These inconsistencies highlight issues with the accuracy of our scam data and suggest that the problem is likely much more dire than reported.

While it’s reassuring that platforms like Gumtree are actively removing obvious bots, when can we be comfortable that the “Johns” of the world are identified and stopped?

How long will it take for the government to disrupt and mitigate the impact of scammers on millions of Australians each year?

[1] ABS, 2024, Personal Fraud Survey, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/personal-fraud/latest-release#methodology

[2] ACCC, 2024, Targeting scams: report of the ACCC on scams activity 2023, https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/targeting-scams-report-activity-2023.pdf

[3] ACCC, 2024, National Anti-Scam Centre quarterly update March 2024, https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/National-Anti-Scam-Centre-in-Action_quarterly-update-October-to-December-2023_0.pdf

[4] Hon Stephen Jones MP, Treasury Portfolio, 2024, Scammer crackdown shows early success as losses fall, https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/stephen-jones-2022/media-releases/scammer-crackdown-shows-early-success-losses-fall

[5] CHOICE, 2024, Passing the Buck: how businesses leave scam victims feeling alone and ashamed, https://www.choice.com.au/-/media/ef2c01fa82c448cda1ad2b8bde1662d3.ashx?la=en.

Consumer Law

September 12, 2024

While there are some positive developments the fragmented approach potentially leaves crucial gaps in protecting Australians' digital rights.

Consumer Law

March 15, 2024

2024 Ruby Hutchison Memorial Lecture